Quantitative Ecology - Data Science - Sustainability

Quantitative Ecology - Data Science - SustainabilitySections

COVID-19 pandemic and global fisheries

Marine protected areas in a changing world

Socio-ecological systems

Improving monitoring programs

Variability in ecological management outcomes

Long-term trends of marine predators

Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

Metapopulation dynamics of small mammals

Environmental variability can occur on daily to decadal time scales. This variability can include natural variation, such as changes in seasons, or anthropogenic events like oil spills. Of course, these various forms of environmental variability shape ecosystems, and, consequently, the human communities that depend on them. In addition, climate change is expected to increase variability and uncertainty of these environmental factors. My research program addresses questions that fall within the Venn diagram above:

Building on my work in both COVID-19 modeling and marine fisheries, I am now collaborating with several people on how COVID-19 might affect fisheries and fishing communities. The last time we experienced a reduction in fishing effort of this magnitude was during both world wars when oceans were effectively closed to fishing. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments have shut down various parts of their economies to promote social distancing. Already, fishing seasons have been cut short or certain types of fishing (e.g. commercial versus recreational) have been restricted. However, these government actions vary between and within countries (White & Hébert-Dufresne 2020). This presents another natural experiment to see how fish populations and fisheries respond to management interventions. Our goal is to understand the downstream effects of these shutdowns on fisheries, fish populations, and the communities that rely on them. If you are interested in contributing to this project please send an email to Easton.White@uvm.edu. We have also built a crowd-sourced database of COVID-19 related effects on fisheries which is being updated here: https://zenodo.org/record/3866189/

We are examining the design of marine protected areas given environmental variability. All over the world, networks of marine protected areas have been established as both a conservation and management tool (Gaines et al. 2010). However, most work to date has ignored the role that variability or uncertainty in designing these marine protected areas (but see Halpern et al. 2006). Variability is important as individual protected areas can serve as an insurance policy for one another. If a population in a particular protected area is devastated by a hurricane, then organisms from another, unaffected population can recolonize that protected area. My current work (available as a preprint below) has focused on building simple, theoretical models to include variability in the design of these protected areas.

White, Easton R., Marissa L. Baskett, and Alan Hastings. 2020. Catastrophes, connectivity, and Allee effects in the design of marine reserve networks. bioRxiv.

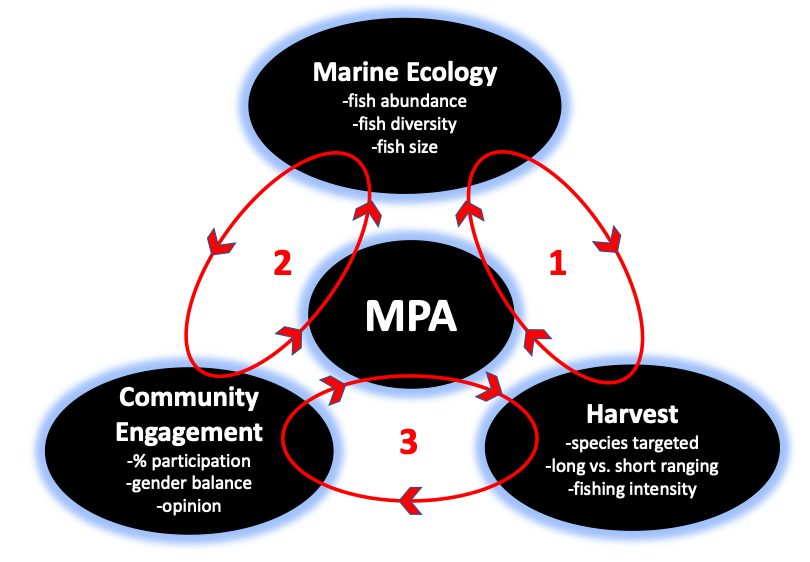

Our work on marine protected areas led to an interdisciplinary collaboration with Drs. Merrill Baker-Medard (social scientist at Middlebury College) and Elizabeth Fairchild (fisheries biologist at the University of New Hampshire).

(CO-PIs) Baker-Medard Merrill, White Easton R., and Elizabeth Fairchild. Socio-Ecological Feedbacks of Marine Protected Areas: Dynamics of Small-Scale Fishing Communities and Inshore Marine Ecosystems. National Science Foundation CNH2: Dynamics of Integrated Socio-Environmental Systems. $602,320. 2019-2024.

Monitoring of populations is a critical aspect of making decisions about the management of species. However, monitoring is often expensive and requires a lot of people-hours. Therefore, it is essential to determine the optimal locations for monitoring, the number of samples to take, and the frequency and duration of monitoring effort.

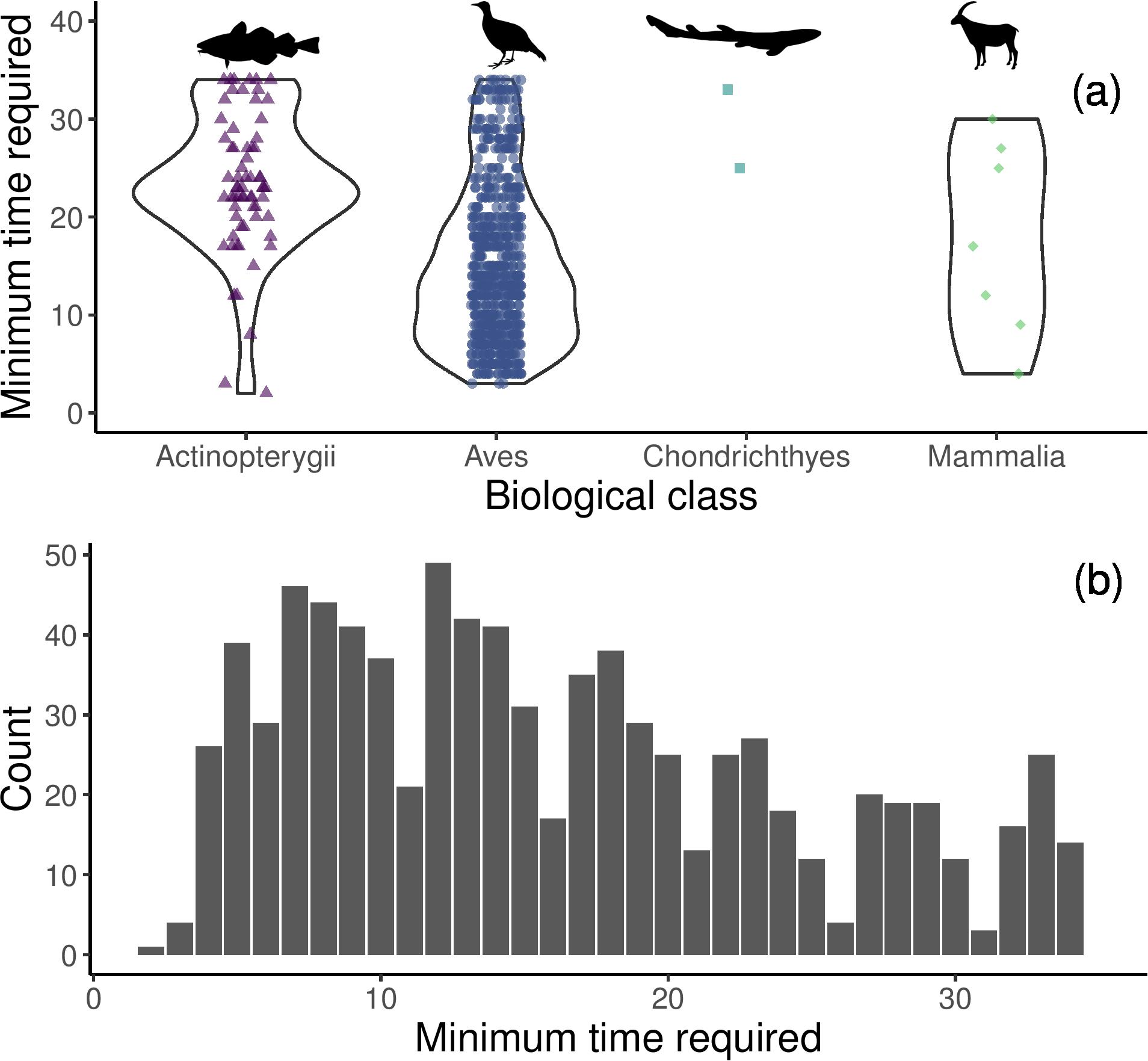

In a recent manuscript at Bioscience (available here), I determined the minimum number of years required to be confident (i.e. have enough statistical power) in a population trend. Using simulations and empirical data from 822 populations, I estimated that 15.9 years on average were required. There was, however, tremendous variation between populations, casting doubt on simple rules of thumb. In a BioScience podcast, I discuss this work and population monitoring in general.

Dr. Stephen Heard (University of New Brunswick), Dr. Auriel Fournier (Forbes Biological Station), and I recently published an article in Conservation Biology that focused on the question of sampling bias in monitoring programs.. We found that bias in the sites chosen for monitoring can lead to overestimates in the long-term population decline estimates.

In a recent preprint, Dr. Christie Bahlai and I examine the various tools available for thinking about improving species monitoring programs. We emphasize the idea of conducting "experiments" with past monitoring programs in order to improve them and design new ones.

Dr. Rosalie Bruel and I applied these techniques to study the optimal sampling requirements and approaches for detecting ecosystem change in plankton communities derived from sediment cores. This work is now available in a recent preprint.

White, Easton R., Kyle Cox, Brett Melbourne, and Alan Hastings. In press. Success and failure of ecological management is highly variable in an experimental test. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

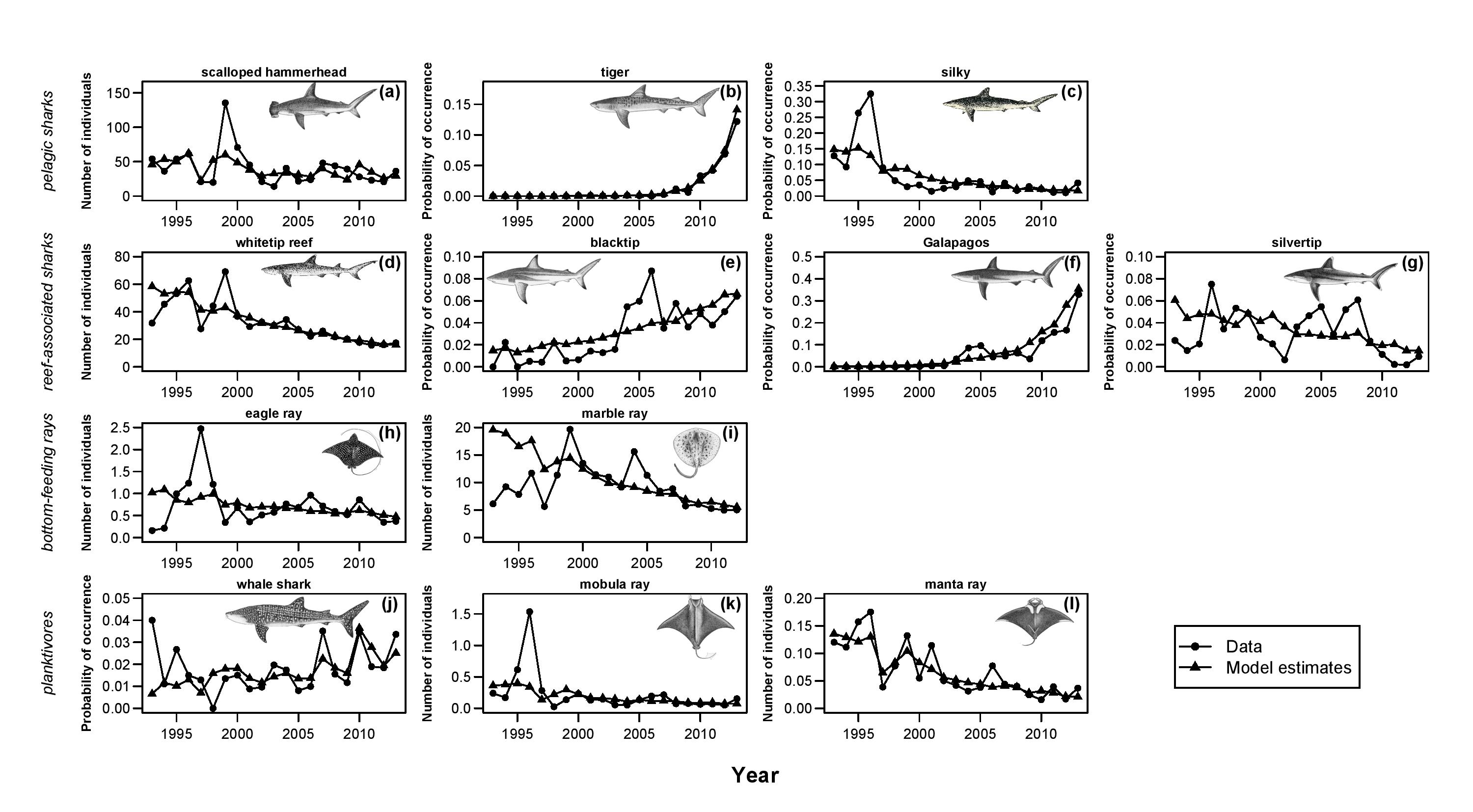

Worldwide, many species of sharks and rays have seen large declines in population size. Approximently, 25% of all chondrichthyan (shark, ray, chimaeras) species around the world are threatened according to IUCN criteria (Dulvy 2014). These species are threatened from overfishing, habitat degradation and pollution. Sharks and rays act as predators and drive population dynamics of species lower in the food chain. (Heithaus et al. 2010). In response to declining populations of sharks and rays, many countries have instituted marine protected areas (MPA). An MPA is a conservation and management tool that is designed to let species recover by providing them with an area of refuge, free from fishing. However, it is not clear if MPAs are effective for large mobile predators, like sharks and rays.

We are studying sharks and rays at Cocos Island. The island is located 550km off of the mainland of Costa Rica. The island has been a marine protected area for the past two decades. We use data collected by the dive company Undersea Hunter, to get a sense of the population status of 12 shark and ray species that are commonly seen at Cocos Island. Here is the paper Shifting elasmobranch community assemblage at Cocos Island – an isolated marine protected area and here is a corresponding press release.

In a related project, I studied long-term trends of lemon sharks found in the Bahamas. We developed a series of mathematical models to better understand the population of juvenile lemon sharks found in the lagoons of Bimini. We found that the variance in population size of juvenile sharks, is mostly driven by the environment. Therefore, predators and food resources may not be as important factors in driving population dynamics as once thought. I combined a mathematical model with field data to better understand a population of lemon sharks in the Bahamas. I found that a simple model could predict the long-term mean of the population size well, but it did a poor job at predicting the variance in population size (White et al. 2014). It turned out that much of the variance in population size could be explained by a few unusual years in terms of the environment.

We study the ecology and evolution of the American pika (Ochotona princeps) living on a metapopulation at Bodie State Historic Park. The metapopulation is comprised of patches made up of abandoned ore dumps. Near the end of the 19th century, pikas colonized these ore dumps creating a metapopulation of about 80 patches. Around 1990, the southern half of the study site had collapsed and few pikas have been censused there since. We developed a simulation model to better understand the dynamics of the Bodie population. We have found that spatial structure (the arrangement of the patches in the landscape) and demographic stochasticity both important aspects of the Bodie site.

These findings have recently been published in Ecology.

Here is a simulation of metapopulation dynamics at Bodie over the last 40 years. The size of the circles represents how many pikas are on a given patch in each year.

I spent a summer at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Vienna, Austria. I led a team of biologists and mathematicians to investigate the evolutionary consequences of changing seasonal regimes due to climate change. This work focused on the collared pika (Ochotona collaris) found in the Yukon, Canada. This work is available as a preprint (White et al. 2018).

In addition to biology-focused work, I have also been engaged in research on pedagogy. This is often termed Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) or sometimes Discipline-based education research (DBER). As a scientist, I view teaching as a highly scientific process. I design and implement experiments in the classroom each time I teach. I then examine the results using various assessments (e.g. pre- and post-assessments, clicker questions, online activities) and refine my teaching approach.

As part of my efforts in teaching a summer biology bridge program at UC Davis, I also assessed student outcomes. These results are being used by the department to improve the biology bridge program in the future.

I am also part of the QuEST Leadership Team at the University of Vermont. QuEST is a PhD training grant focused on quantitative skills, applied problem solving, and diversity. Part of my responsibility is to assess student learning in the core course titled, Foundations of Quantitative Reasoning. The course involves inquiry- and team-based activities as well as active learning.